Every so often, when the data comes in lower, Demand Side rears its head and repeats its forecast: Bouncing along the bottom with downside risks. Actually, we raise our head at other times as well, just not very long.

In any event, today's podcast looks at some of the weakening data and some of the risks.

Listen to this episodeTHEN, the interest rate has been the focus of Fed policy, now and forever. Some have called Ben Bernanke a Keynesian, apparently with this preoccupation with the interest rate. Never mind Bernanke is a disciple and acolyte of Milton Friedman, the anti-Keynesian warrior. But indeed, Keynes viewed the interest rate as the key to explaining investment in normal times. The coordination, I guess you might call it, of the interest rate with what he called the marginal efficiency of capital -- the expected return on capital -- was no doubt at the center of the General Theory.

We look, with Keynes, at normal times, the classical interlude and back beyond into Mercantilism, where again, a high interest rate was not welcome. Is Bernanke a Mercantilist?

And before we omit it again, visit us in Seattle May 23rd for a discussion of "Money, Monetary Policy and Financial Repression" with Steve Keen and Gerard Fitzpatrick. Details of that event, registration, at SteveKeenInSeattle.com. Low price. Lunch included. Seattle's Town Hall. Also see the evening talk by Steve. Same location.

Let's start about the data. Check out the charts (or is it graphs?) online at DemandSideEconomics.net, the official transcript site. Once we get past Steve Keen in Seattle, we'll start posting again at reMacro.

Data one. The average of Fed manufacturing surveys has dipped again -- the average of all the surveys -- into negative territory again. The latest being the Dallas Fed, which reported that "Growth in Texas Manufacturing Activity Stalled" in April. Their general business activity index plummeted from 7.4 on the plus side to minus 15.6. The employment index was up. The hours worked index down.

Inflation continues to come in below the Fed's target. Deflation? Core PCE is 1.1 percent year over year in March. But cheer up, Ben, house prices at Case-Shiller showed a 9+ percent increase year over year. All that interest rate subsidy to homebuyers is doing something. Note: Case-Shiller is a three-month moving average and reflects conditions in February better than March. Also note that the affordability index is still dropping, even as prices rise, and make what you will of that.

I hear somebody objecting: This is all very well and good, you are saying, that things are weakening in the real economy, and Demand Side did kind of predict a post-election slump, but what about your claim that there has been no recovery?

True. We have never admitted recovery. We are recovery deniers. The business cycle is broken, we have said it again and again. There is no way up absent investment in people and investment in infrastructure. That has not recovered. Housing came down 50%. If it goes back up 50% it is still down 25%. And it has not gone up 50%. Government continues to contract. Q3 2012 -- presidential election campaign quarter -- was the only net positive government number since Q2 2010. Now it's back in the red. With the sequester and fiscal prudence in the form of cutting aid to the most vulnerable, combined with the ongoing shrinkage of local and state government, we have downside risks on the government investment side.

And private investment? A hair on the positive side, in gross terms. Net, I don't think it is positive. Why would it be? Capacity utilization is low, prospects for profit are low because of tepid demand. So where is a business cycle without investment?

We suggest it is broken.

In the March GDP numbers, the contribution to investment by business inventories is what saved the day. Let's look at that report more closely with the help of Douglass Short at Consumer Metrics.

2.5% GDP growth was reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. This was below Wall Street consensus of 2.9 to 3.5 percent. Consumer spending was up -- thanks mostly to non-discretionary rents and utilities. Fixed investment -- gross, not net -- was positive, barely, at 0.53 percent. And inventories were back up from Q4 2012, and (quoting Davis) "arguably provided all of the quarter-to-quarter improvement in growth."

Wait, you're back to the short term, you say.

Fair enough, but before we leave it, realize that those numbers are real gross numbers. They are (1) moved by inflation assumptions, and (2) not net.

Inflation assumptions by the BEA impact the "real number." The BEA deflator was 1.2 percent. Similar to the 1.1 percent Core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure) number above. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a 2.1 percent annualized inflation rate, GDP with that adjuster would not have been 2.5, but rather 1.6.

and (2) Gross is not net.

But just subtracting inventories to get "real final sales of domestic product" dropped growth to 1.45%.

Four years into recovery/expansion, and employment is still below its previous peak. Still net negative jobs. You know that.

But look here. Real per capita disposable income, as Davis says, "took a monumental hit: It dropped by an annualized $498 from quarter to quarter. Real per capita disposal income is now down $123 annually from Q1 2011 -- a full two years ago, and one percent below its reading in December 2007. That is more than five years ago.

Why are employment and per capita incomes not the determinants of recession in an economy where investment and the business cycle are broken? They should be.

Jobs are job one, everybody says it. Phooey. We could employ, what?, six or eight million more people a year on half of what the Fed is paying for MBS and Treasuries. It would get a lot of people off assistance and back into generating revenue for the government. Build stuff. Put people to work. Maybe get teachers, police, firefighters back on the job. Positive for revenues.

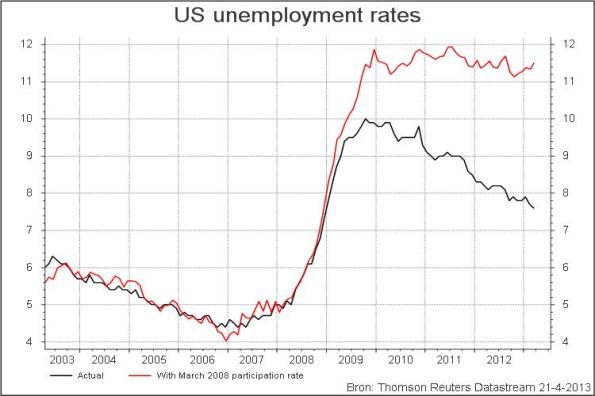

Now, down here on the transcript is the chart that connects employment to unemployment. As you know, the unemployment rate is falling, but not because people are hiring so much as because people are dropping out of the labor force. Employment is the numerator. The work force is the denominator. Here's the chart (or is it graph?) I wish I had done. From Merign Knibbe at RWWER. The unemployment rate as it would have been if the participation rate had held at its March 2008 level.

Unemployment would have spiked -- this is headline, not all-in U-6 -- would have spiked to just short of 12%, well past the 10% top at the end of 2009. It would still be between 11 and 12 percent. Instead, as we know, official headline unemployment is now at 7.6 percent. All due to the fall in the participation rate.

Combine this with per capita income, down, and with the income disparity growth, the median -- the person with 50% of the population above and 50% below, the middle of the middle class, has undoubtedly dropped as well.

So we are in trouble.

I promised a bit on Keynes and interest rates, and that is getting squeezed into even more little. But first a note on the continuing Rogoff-Reinhart debacle.

We pulled no punches last week. New research, or at least newly announced research, from the University of Missouri Kansas City confirms a key part of our criticism -- that the causal arrow is more likely in the opposite direction than that which Rogoff and Reinhart suggested and the right wing pundits promoted. That is, a careful treatment of the data indicates high debt to GDP is caused by low growth. NOT low growth by high debt to GDP.

Of course, Steve Keen and Richard Koo and others would show that the public debt is a sideshow compared to the enormous private and household debt.

[Did I mention that Steve Keen is in Seattle May 23? See SteveKeenInSeattle.com.]

But Rogoff and Reinhart protest. They were back in the New York Times op-ed pages complaining about how they have been treated. Quoting "Our view has always been that causality runs in both directions, and that there is no rule that applies across all times and places."

Phooey. The opportunity was there to join with those who made this criticism to begin with. Instead Rogoff and Reinhart became media stars. They did not use it to stake out this defensible position. Public debt was the cause of slow growth, actually of contraction. I didn't hear an echo of the correlation is not causation argument at the time. Those who tried to make the point were pitied as poor sports and ignorant of hard facts.

What is the point of aggregating all that data into a 90% figure if the rules don't apply to the individual data?

[And here is my "oops." In my previous rant, I said that 17th century monarchies were being compared to 20th century industrial democracies. True in the broadest sense, but not so for the critical 90% context -- when it is the annual economic growth across nations in the 1945-2009 time frame. Which still compares postwar ... never mind, my bad.]

"... the Rogoff and Reinhart affair shows how slow economists are to realize that their data may be dodgy, but to my mind that is insignificant compared to how slow they are to realize that their theories are dodgier still.

A defining feature of mainstream economic modelling is the belief that the economy is stable: given any disturbance, it will ultimately return to a state of tranquil growth. Mainstreamers argue over how fast this will happen: Chicago/Freshwater/New Classicals argue it adjusts instantly, while Saltwater/New Keynesians say it will take time because of ‘frictions’ in the economy’s adjustment processes. But they both take the innate stability of the economy for granted, and this belief is hard-coded into their mathematical models.

This stability is also seen as a good thing – so much so that anything which obstructs it being achieved should be removed. They argue over policy in a crisis like the world’s current one, with New Classicals falling firmly into the ‘Austerians’ camp while New Keynesians favor fiscal stimulus, but they speak almost as one in favor of eliminating monopolies, reducing union power, deregulating finance – or they did before the financial crisis came along.

One would think that after as disturbing an event as the Great Recession – and let’s call it as it is now, the Second (or perhaps Third) Great Depression in Europe – that this belief in the innate stability of capitalism might be at least reconsidered by the mainstream. But though they’re willing to tinker at the edges, their core vision of the economy as being either in or near a stable equilibrium remains an unchallenged mantra.

So we got to Steve Keen, remember May 23, Town Hall. But we didn't get to John Maynard Keynes and the interest rate. Let's do that quickly.

Currently Ben Bernanke and the Fed have determined that the only route to recovery is a zero percent interest rate. Wall Street looks past the phenomenally low rate, now several years on, sees some breathing in the housing market, and determines we are on our way up and onward.

John Maynard Keynes in the General Theory makes much of the interest rate, which he defines as the price of not hoarding, and its relationship to the marginal efficiency of capital, which he defines as the expected return on capital -- as I understand it. They will tend to come in about the same.

Problem. Well, first problem, the central bank has taken over the interest rate. Second, people are hoarding, corporations are hoarding, the politics wants the government to hoard. So the interest rate is not working as the price of not hoarding.

Second problem, EXPECTED return. Entrepreneurs in this climate have no idea what the expected return is. They do not invest because they think it may be less than the interest rate. Demand is not certain or strong. What if inflation kicks up? What if deflation kicks up? A lot is made about regulatory uncertainty, but this is an excuse, or rather a method of blaming.

So the interest rate is not useful with capitalists in this context. Keynes advocates government investment, or "socialization of investment," which is not quite the same thing. The post-war support for housing, which continues to this day, is a form of socialization of investment. Keynes is specific, though I am not quoting him here, that the interest rate as a stimulus to investment can break down. We heard Michal Kalecki last time describing how the state of confidence of business is a back door way to manipulate.

Before we take it too far, let's get the moderating voice of Keynes himself in here:

page 378

In some other respects the foregoing theory is moderately conservative in its implications. For whilst it indicates the vital importance of establishing certain central controls in matters which are now left in the main to individual initiative, there are wide fields of activity which are unaffected. The State will have to exercise a guiding influence on the propensity to consume partly through its scheme of taxation, partly by fixing the rate of interest, and partly, perhaps, in other ways. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment; though this need not exclude all manner of compromises and of devices by which public authority will co-operate with private initiative.Interestingly, regarding the interest rate, Keynes found much to admire in the pretty much discredited Mercantilist approach. The object of each government and nation was to gain control of the measure of wealth.

For in an economy subject to money contracts and customs more or less fixed over an appreciable period of time, where the quantity of the domestic circulation and the domestic rate of interest are primarily determined by the balance of payments, as they were in Great Britain before the war, there is no orthodox means open to the authorities for countering unemployment at home except by struggling for an export surplus and an import of the monetary metal at the expense of their neighbours. Never in history was there a method devised of such efficacy for setting each country’s advantage at variance with its neighbours’ as the international gold (or, formerly, silver) standard. For it made domestic prosperity directly dependent on a competitive pursuit of markets and a competitive appetite for the precious metals. When by happy accident the new supplies of gold and silver were comparatively abundant, the struggle might be somewhat abated. But with the growth of wealth and the diminishing marginal propensity to consume, it has tended to become increasingly internecine. The part played by orthodox economists, whose common sense has been insufficient to check their faulty logic, has been disastrous to the latest act. For when in their blind struggle for an escape, some countries have thrown off the obligations which had previously rendered impossible an autonomous rate of interest, these economists have taught that a restoration of the former shackles is a necessary first step to a general recovery.

In truth the opposite holds good. It is the policy of an autonomous rate of interest, unimpeded by international preoccupations, and of a national investment programme directed to an optimum level of domestic employment which is twice blessed in the sense that it helps ourselves and our neighbours at the same time. And it is the simultaneous pursuit of these policies by all countries together which is capable of restoring economic health and strength internationally, whether we measure it by the level of domestic employment or by the volume of international trade.Okay, enough, more than enough for today. See the charts, er, graphs at the bottom of the transcript.

No comments:

Post a Comment